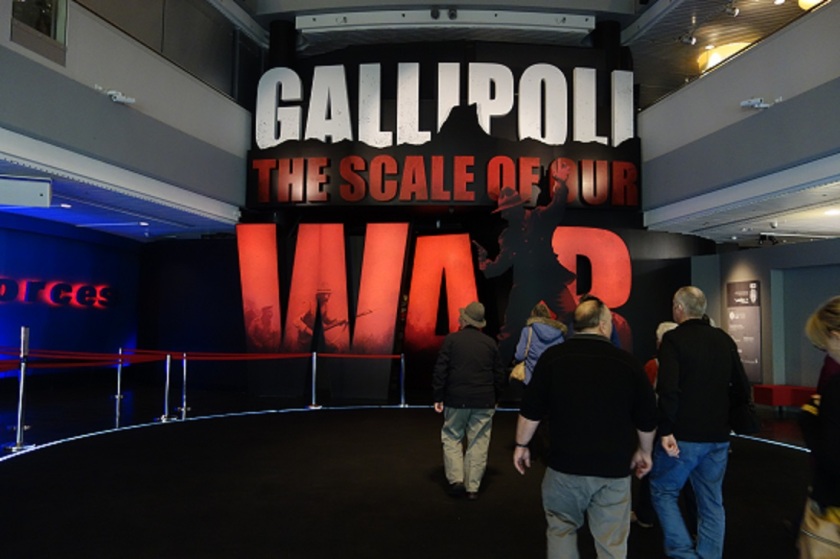

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (usually called Te Papa) is situated on the waterfront on Wellington Harbour. I visited the exhibition “Gallipoli: the Scale of Our War”.

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (usually called Te Papa) is situated on the waterfront on Wellington Harbour. I visited the exhibition “Gallipoli: the Scale of Our War”.

Such exhibitions blend ideas, information and emotions; conveying something of the personal experience of the individuals to an observer who is 100 years distant to the whole experience, not only of war, but of place and the times themselves. This game with my emotions cut quickly to the core. To blend the personal with the past is a powerful tool in myth creation.

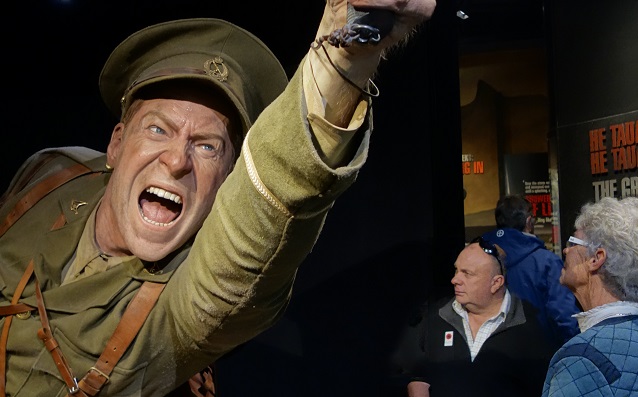

On entering the first of a series of dimly-lit circular chambers the visitor is confronted with an illuminated 2.4 times life-sized model of the wounded New Zealand soldier, Spencer Westmacott, face wrought with tension, firing a revolver over your head. You can circle the figure, and examine in forensic detail the dirt, soil, torn cloths, the bleeding wounds on the knee and hand and sink yourself into this very moment in time. The figures themselves are of exquisite detail; 24,000 hours in their creation; every hair follicle showing. The surrounding walls have the story drawn from his diary, and record time, place, objects, action and fate. Part of this is displayed in small exhibition cases containing confirming evidence, another part of the wall, displays a moving finger of hand-writing of the diary entry, which is read aloud over the soundscape of the battle.

The exhibition leads you through six such tableaus, interspersed with hundreds of photos, personal momentos and personal tools of the waring trades (rifles, bayonets, trenching tools, bandages etc). Small sections deal with global geopolitics, domestic politics, Maori involvement in this European war, and including that the Turks were battle hardened and were defending their own territory from foreign invaders.

The second tableau is also confronting; an army doctor, Percival Fenwick, crouched over a fallen blood-stained body; the unknown soldier, face covered with a rough blanket. The doctor’s face is a masterpiece of expression: you can read resignation, anguish, reflection and exhaustion. His words, moving across the wall, convey his personal horror of experiencing the slaughter. We are taken far beyond the personal, out of our comfort zone, to face the costs, futility and scope of such enterprises.

There is a small accompanying interactive where you can choose your weapon: shrapnel, bullet, grenade or flying metal and watch in slow-motion as it does its particular damage to a life sized x-ray scan of a human body, followed by medical case reports of real people with such injuries.

There is a small accompanying interactive where you can choose your weapon: shrapnel, bullet, grenade or flying metal and watch in slow-motion as it does its particular damage to a life sized x-ray scan of a human body, followed by medical case reports of real people with such injuries.

Along the way we pick up the narrative threads of this unfolding disaster. The first day of the landings made progress up narrow gullies to the surrounding ridge until fierce resistance was met and the advance stopped. The commanders considered withdrawal. Instead, over the next eight months, no further progress was made and a stalemate was in place. Both sides dug in and advances by either side were reciprocated and measured in blood-soaked metres. At times, front-line trenches were only 6-10 feet apart. Deaths rates in battles were expressed in terms of numbers of deaths per yard gained or per acre of ground. It was difficult to cross no-man’s land without stepping on a corpse.

Gradually conditions worsened, casualties in both sides mounted, life was lived in dugout hovels, the wounded, flies, lack of sanitation, lice, poor water and food, the stench of rotting corpses and shit, broken supply lines, many brave actions by both sides, suicidal charges, gallant defences to the last man, attrition and death by shell, shot and disease.

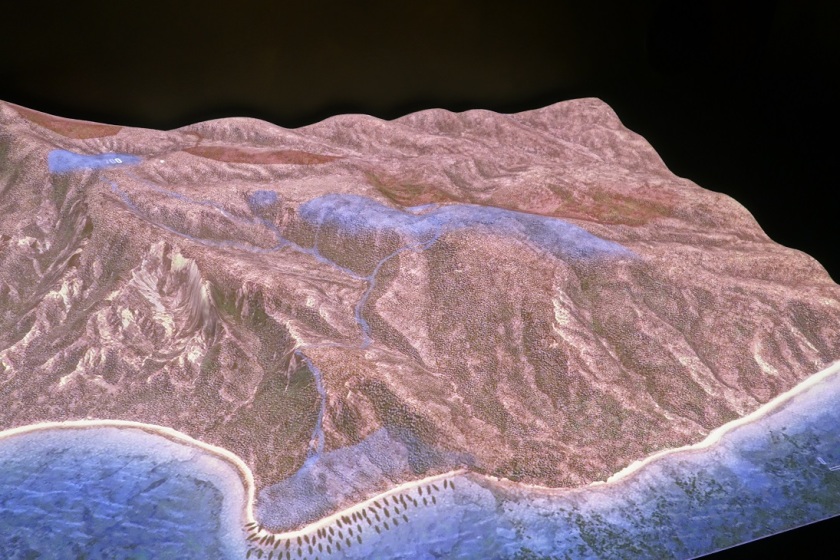

3-dimensional scale models of the landscape glow with moving coloured amoeba-like blobs (we are blue, they are red) portraying the ebb and flow of both sides over time. Like arterial and venous blood flowing through capillaries, bleeding to death, down to sea.

There was a major NZ attempt to break the stalemate in August, at a ridge called Chunuk Bair (Australia had hers at Lone Pine). This had elements of surprise and initial success and at the great cost of lives, moments of fatal hesitation, more gallant suicidal charges, and ultimately more death and destruction.

There was a major NZ attempt to break the stalemate in August, at a ridge called Chunuk Bair (Australia had hers at Lone Pine). This had elements of surprise and initial success and at the great cost of lives, moments of fatal hesitation, more gallant suicidal charges, and ultimately more death and destruction.

While the New Zealand soldiers captured their objective (largely at night by bayonet), the supporting British forces never arrived and the position had to be abandoned. Of the 700 New Zealand soldiers involved, only 76 were not killed or wounded on that day. The NZ commander, Lieutenant Colonel William Malone himself was killed by a shell fired in support by a British warship and, perhaps worse, he was subsequently held responsible for the failure of the battle by British command, a claim resolutely disputed by contemporary historians.

Among the most moving experience is the re-created sandbag shelter where just hours before the Kiwi assault on Chunuk Bair, Malone penned the last letter to his wife, Ida. Only three at a time can fit inside to see and hear the reading of the following:

‘My Sweetheart:

In less than two hours we move off to a valley, where we will be up all night and tomorrow in readiness for a big attack, which will start from tomorrow night. Everything promises well and victory should rest with us. God grant it so and that our casualties will not be too heavy. I expect to go through my dear wife. If anything untoward happens to me there are our dear children to be brought up. You know how I love and have loved you, and we have had many years of great happiness together. If at any time in the past I seemed absorbed in ‘affairs’, it was that I might make proper provision for you and the children. That was due from me. It is true that perhaps I overdid it somewhat. I believe now that I did, but did not see it at the time. I regret very much now that it was so and that I lost more happiness than I need have done. You must forgive me; forgive me also for anything unkindly or hard that I may have said or done in the past.I am prepared for death and hope that God will have forgiven me all my sins. My desire for life – so that I may see and be with you again could not be greater, but I have only done what every man was bound to do in our country’s needs. It has been a great consolation to me that you approved my action; the sacrifice was really yours. May you be consoled and rewarded by our dear Lord’

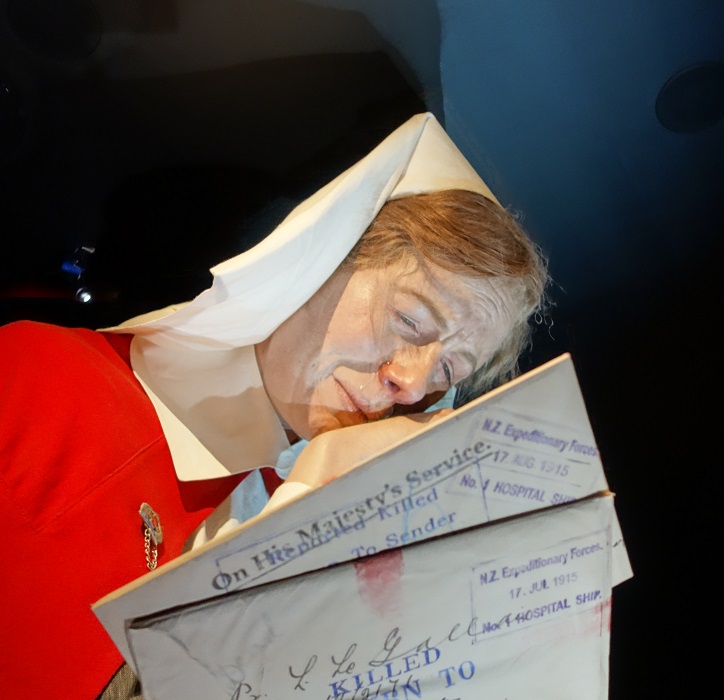

The close personal contact with grief is exemplified by the figure of the nurse, Lottie Le Gallais, who served on a hospital ship, weeping on receipt of her letters to her brother, returned as he had been killed.

The curious moralities of war and death are exemplified by the figure of Jack Dunn, a courageous soldier who was court-martialled for falling asleep on guard duty; according to the Army manual this was a capital offence. He was convicted and sentenced and given his record, the sentence was overturned. He also later died at Chunuk Bair.

The ferocity is exemplified by two men manning a machine gun in the face of an assault while a third lies dead at their side. There were many instances where positions were held only because of the outstanding bravery of individuals.

The ferocity is exemplified by two men manning a machine gun in the face of an assault while a third lies dead at their side. There were many instances where positions were held only because of the outstanding bravery of individuals.

After Chunuk Bair there was another major attack past all limits of logical comprehension made under distant orders, men were pushed beyond the limit if their exhaustion; again with large losses, illustrating the crazy futility.

Finally, probably the most notable victory was the silent and strategic withdrawal of 46,000 men over 5 days; they slipped away into the night while giving the impression the landscape remained occupied.

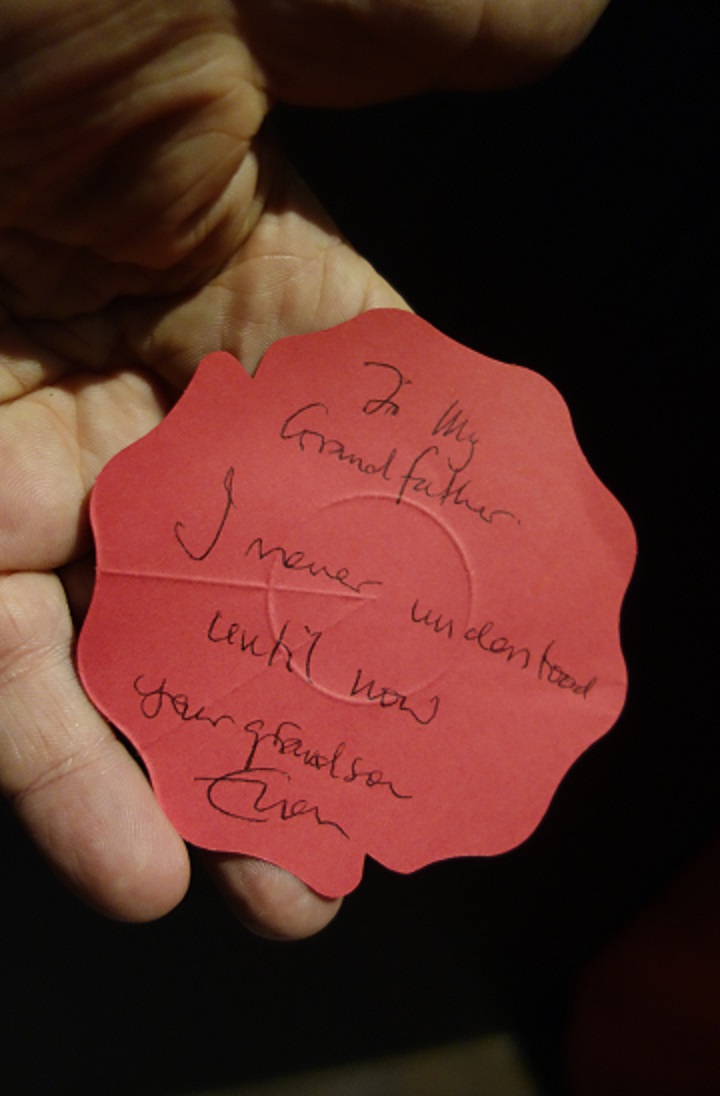

But emotions are not over yet; there is one final twist of the bayonet. On leaving visitors are invited to write a note on a red paper poppy to a fallen person.

This poppy is placed in a pool-like space around the base of an exhausted, advancing soldier.

All very emotional stuff; there is little military glory or honour, no military victory, only some understanding that our forefathers had an ability to sustain and fight on and frequently die in these circumstances.

I am not sure of the origin of ANZAC day; the exhibition simply claims “On April 25th 1916, our first Anzac Day, we played footy in a village and drank to dead mates”. More official war histories note that by 1916 New Zealand had by gazetted the 25th April as an official day of remembrance of the war dead back home (and something similar in Australia), with soldiers in France and the UK wanting to celebrate this together, as church-led services precluded the mixing of catholics and protestants.

I have never been to a museum exhibition which focusses so personally on a war and told through the experience of six people. In uses fragments of time, largely devoid of global geopolitics, the racism, colonialism, and imperialism of its time, or the subsequent aftermath. In some ways that is a pity; while we honour the individual we fail to appreciate the flaws in the wider frame that both made this possible, nor do we question the consequences.

If it is at all true, and there is no evidence to doubt it, then there was something special, or at least different, about standards of behaviour which would subsequently be described as ‘magnificent’ where men were repeatedly prepared to act as some primal unit and repeated risk their own lives and repeatedly paid for this with death and disfigurement. Men fighting fellow men, doing whatever it took to kill and survive, and not infrequently honouring these characteristics in the enemy if they did the same, more so for the Turks than for the Germans. This was a manly game, that drew out of individuals the long held classic virtues, the characteristics of a warrior, death before dishonour. One might argue that due to their socialisation and pressures they had little choice, there was no option to ‘beam me up Scotty’. However, it could also be argued that in both sides there was the spirit of pursuing a collective social goal and such a spirit, is rare if not absent today, in how we live and reward and prosper. It is in stark contrast to the fascination with the self, the pursuit of individual pleasures and in generating wealth and possessions insanely past our own requirement and blind to the capacity of a world to sustain these for future generations. Such a terrible waste of life, which continued and scarred all the nations involved. How many men were led to an an unknown and ‘honorable death’ when they could have lived and contributed so much more to social change, or whatever virtue you wish to nominate.

Within the context of what happened in this place, we can question what it is that makes men follow other men and what are these core qualities of leadership that are displayed, however well or badly such sacrifice is exploited.

ANZAC will always be a legend; we will never own, know or experience the events that involved tens of thousands of people 100 years ago. The French, with their long military history, lost more people in the same invasion of the Dardanelles than we did and to them it is a best-forgotten military debacle; for us remains a mystical event contributing to the abstraction of nationhood.

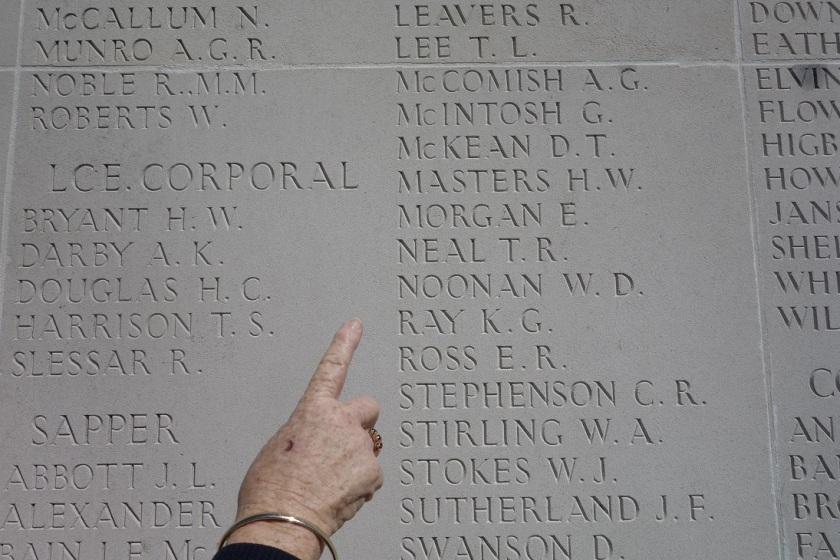

My grandfather (my mother’s side), George James Sutherland of the Otago Regiment died of wounds a few weeks after his evacuation from Gallipoli in August 1915. He left behind a young wife and two young children; his death greatly affected the passage of all their lives. His letters to his wife were lost in a house fire a few years after this; those to his mother survived and are transcribed by me here. His final letter, 15th August contains the lines “We are expecting a big smash-up in a day or so and I hope my luck holds good though a big lot of us are bound to go under. However we are all keen for it and from what we learn Otago is to take the lead and have the place of honour.”

I also visited the official war Museum up the hill in Wellington. It is old-school, with a catalogue of uniforms, big guns, maps, street scenes, real tanks, many pictures, lists of war dead and life-sized tableaux. Somehow, emotionally, you walk out through the same door as you entered through.

The June-July 2016 edition of the Australian Book Review contains a review by Andrea Goldsmith of “In Praise of Forgetting: Historical Memory and its Ironies’ by David Rieff. Goldsmith notes “individual memory degrades very quickly, while official memorising is a tool in service of ideological and cultural currents … official remembrance is big business these days”. Rieff accuses even the Holocaust Museum in Washington of being “book-ended in kitch”. [Goldsmith] rationalised the motivation that by “promoting personal involvement in the (long past) events portrayed, visitors will be motivated towards a better understanding”.[Goldsmith] regrets the loss of imagination itself as the vehicle for understanding the past, although later comments that memory itself is a form of imagination. Rieff apparently advocates forgetting as a way for individuals to move on from past atrocities, using personal strength and resilience. He claims it was the children and grandchildren (and their own brand of narcissistic remembrance) who dragged the survivors back to Auschwitz. I have bought the book but so far have not read.

In terms of this war, I suspect people who where there did not talk about it (bit like the 60s really) for many reasons; or at least only in code with those who shared it. Its magnitude is overwhelming. Loss, comradeship, love and sacrifice are a heady personal mix and easily distorted by the same social forces that led to these conflicts, wrote history and benefitted at a national scale. It is prudent to privately remember the forces that tore apart families of people we know and our own families and these effects can never be denied or forgotten.

This one seems to echo the anguish and carefully considered voice of a people who did not want the war (they considered themselves neutral until invaded) and suffered deeply as a consequence. Statistically, their percentage male death rate (~2%) was less than the UK, Australia or New Zealand, (all around 10%). Not that 2% of a male population is trivial, particularly as much of this occurred early in brave attempts to protect their country which were simply out-manned and out-gunned. There were also terrible retributions on the civilian populations. More than a million fled. Many cities were destroyed. The Belgiums flooded large parts of the countryside by opening the dykes and these regions remained un-invaded for the war.

This one seems to echo the anguish and carefully considered voice of a people who did not want the war (they considered themselves neutral until invaded) and suffered deeply as a consequence. Statistically, their percentage male death rate (~2%) was less than the UK, Australia or New Zealand, (all around 10%). Not that 2% of a male population is trivial, particularly as much of this occurred early in brave attempts to protect their country which were simply out-manned and out-gunned. There were also terrible retributions on the civilian populations. More than a million fled. Many cities were destroyed. The Belgiums flooded large parts of the countryside by opening the dykes and these regions remained un-invaded for the war.

It might seem a bit weird to have a post just about cemeteries and memorials, that is, until you have been here. Then they become a topic and an object in themselves.

It might seem a bit weird to have a post just about cemeteries and memorials, that is, until you have been here. Then they become a topic and an object in themselves.

Literally some corner of a foreign field …. one of 18 within 3 kms of Beaumont-Hamel

Literally some corner of a foreign field …. one of 18 within 3 kms of Beaumont-Hamel

The (British) Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme is the largest of its type in the world. It sits atop a hill and commands the surrounding farmland. It is constructed as a towering series of arches, the lower walls of which contain the names of over 72,000 British and South Africans who have no known burial site. I have no idea if this is aesthetically successful, it is impressive in its sheer imposing-ness, but i am not sure what it is meant to say. It reminds me how much I like the US Vietnam memorial in Washington, whose the single long sloping wall of black marble evokes the enormity of the campaign and moves people to tears.

The (British) Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme is the largest of its type in the world. It sits atop a hill and commands the surrounding farmland. It is constructed as a towering series of arches, the lower walls of which contain the names of over 72,000 British and South Africans who have no known burial site. I have no idea if this is aesthetically successful, it is impressive in its sheer imposing-ness, but i am not sure what it is meant to say. It reminds me how much I like the US Vietnam memorial in Washington, whose the single long sloping wall of black marble evokes the enormity of the campaign and moves people to tears.

New Zealand has a relatively modest monument at Longueval, in the form of an obelisk, across the base is inscribed this poignant line. We were there alone on a cold windy day, and it seemed even more true.

New Zealand has a relatively modest monument at Longueval, in the form of an obelisk, across the base is inscribed this poignant line. We were there alone on a cold windy day, and it seemed even more true.

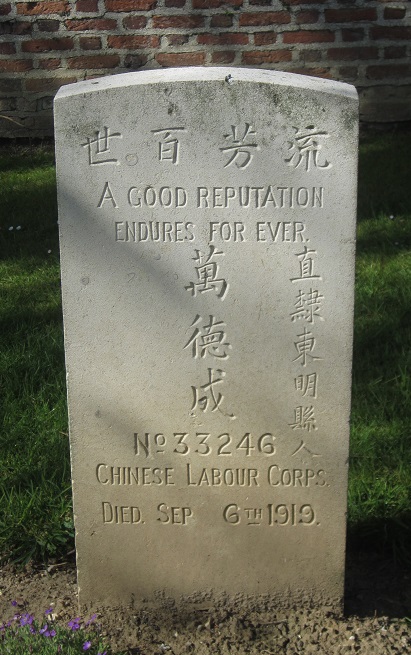

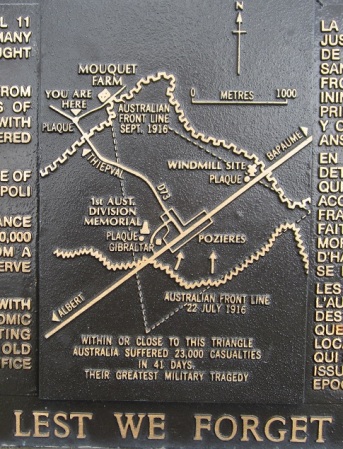

town of Pozieres in the Somme in 1916, Australian troops suffered 23,000 causalities, including 7000 dead in 41 days.

town of Pozieres in the Somme in 1916, Australian troops suffered 23,000 causalities, including 7000 dead in 41 days.

The Windmill site, marked with only a plaque and flags. Ironically, the background is now filled with wind turbines.

The Windmill site, marked with only a plaque and flags. Ironically, the background is now filled with wind turbines.

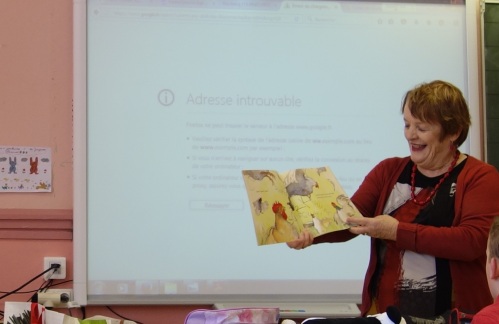

d a class of 25 7-8 year old children Banjo and Ruby Red and gave copies of other books. The teacher provided a language and action translation of dogs bark, chickens squark etc. The rhythms may have been lost in translation (wouf, and cheep), but not the concepts, or the fun.

d a class of 25 7-8 year old children Banjo and Ruby Red and gave copies of other books. The teacher provided a language and action translation of dogs bark, chickens squark etc. The rhythms may have been lost in translation (wouf, and cheep), but not the concepts, or the fun. ou ? How long does it take to fly here? and others.

ou ? How long does it take to fly here? and others.

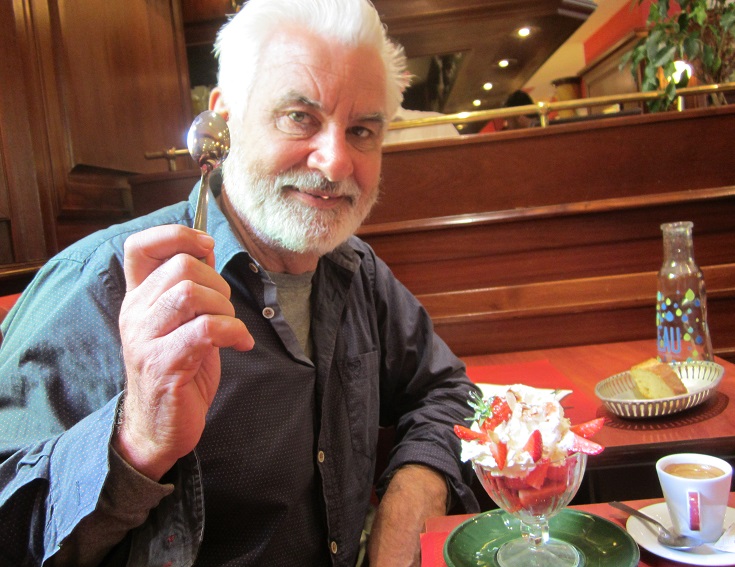

Albert is the closest major town to where we live and has shops and on Saturdays a market. It may seem strange but none of the small villages around here appear to have any shops, indeed most of these small towns appear strangely deserted. That is mystery for another time.

Albert is the closest major town to where we live and has shops and on Saturdays a market. It may seem strange but none of the small villages around here appear to have any shops, indeed most of these small towns appear strangely deserted. That is mystery for another time.